"The most difficult thing is the decision to act, the rest is merely tenacity. The fears are paper tigers. You can do anything you decide to do. You can act to change and control your life; and the procedure, the process, is its own reward." Amelia Earhart

The tragic story of this fearless, pioneering woman has inspired many over the years. She was intelligent, enterprising and adventurous, and she inevitably became my heroine early in life.

Of German descent, Amelia came into the world on the 24th July 1897 in Atchison, Kansas. Possessing a boundless spirit of adventure, the freckle-faced trailblazer enjoyed an idyllic childhood with her younger sister Grace. “Meeley” and “Pidge”, as they were endearingly nicknamed, used to embark on great adventures every day, exploring, climbing trees or “belly-slamming” a sled down a hill.

After graduating from high school in 1916, her quest for an interesting career made her consider film direction and production, mechanical engineering, management, advertising and law. However, her destiny cards had already been dealt and she was subsequently led into the path of aviation. During World War 1, she trained as a Red Cross nurse's aide, and whilst she worked there, she listened to stories from military pilots. This, undoubtedly, helped her develop a keen interest in flying.

Amelia's big chance came in 1928, when she was asked by fellow pilot Amy Guest if she would like to join Wilmer Stultz and Louis Gordon on their transatlantic flight. The journey was a success, landing in South Wales just over 20 hours later. Amelia's role, aside from being a passenger, was to keep the flight log. On an interview after they landed, she said, “Stultz did all the flying – had to. I was just baggage, like a sack of potatoes....maybe someday I'll try it alone.”

Then on the 11th January 1935, Amelia pioneered a solo flight from Honolulu to California on a Lockheed Vega 5C. This route had been attempted by others unsuccessfully, but her voyage was so smooth and straightforward, it even gave her time to relax and tune in to the broadcast of the Metropolitan Opera from New York in the few hours before landing.

She accomplished two more solo flights that same year, from Los Angeles to Mexico City in April and from Mexico City to New York in May.

In preparation for her intended World Flight in 1937, Amelia and her crew flew from California to Hawaii on the 17th March. They encountered a few technical problems, the Electra had to be serviced and they eventually resumed their journey three days later from Pearl Harbour. However, they met with even more adversity. As they were taking off in the direction of Howland Island (a small Pacific island), the forward landing gear came apart after an impromptu ground-loop, the propellers slammed the runway and the aircraft drifted on its belly. After the plane was shipped off for repair, the third crew member, Manning, broke off his affiliation with Earhart and Noonan, saying there had been just too many setbacks. Neither Earhart nor Noonan were skilled radio operators, circumstance which likely sealed their fate later on...

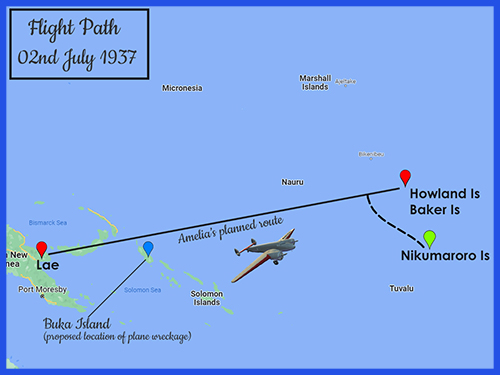

Subsequently, after an unreported flight from California to Florida, Amelia declared her plans to circumnavigate the globe, and on the 01st June, Amelia and Fred Noonan departed from Miami. The route took them via South America, Africa, the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia and, with only another 7,000 miles left of their 29,000 mile voyage, they finally arrived at Lae, New Guinea on the 29th June. This last portion of their adventure would take them over the Pacific Ocean.

The United States Coastguard (USCGC) had the task of keeping radio contact with Earhart and Noonan once they reached the vicinity of the island. However, due to some confusion or several mistakes, it is not clear which, the approach to the island utilising radio navigation unfortunately failed.

It appears Amelia had had very little training on the direction-finding system that had been incorporated into the plane prior to their departure, and it seems that her lack of understanding was evident.

Close to about one hour after Amelia's last documented message, an extensive search conducted by USCGC ensued, covering an area north and west of Howland Island. The United States Navy contributed to the search for the next three days, and on the fourth day, the USS Colorado was ordered to take over the coordination of the entire search.

In spite of the thorough sweep of the area, including various other islands in the group, the outcome was unsuccessful. The infamous Gardner Island, which had been uninhabited for more than 40 years, was also scanned comprehensively - to no avail. The resulting report read “Here signs of recent habitation were clearly visible but repeated circling and zooming failed to elicit any answering wave from possible inhabitants, and it was finally taken for granted that none were there.

The lagoon at Gardner looked sufficiently deep and certainly large enough so that a seaplane or even an airboat could have landed or taken off in any direction with little if any difficulty. Given a chance, it is believed that Miss Earhart could have landed her aircraft in this lagoon and swum or waded ashore”. Even back then, the odds seemed to have been stacked highly in favour of Gardner Island...

The joint search efforts conducted by the aircraft carrier USS Lexington, the battleship USS Colorado, the USCGC, the Japanese oceanographic survey ship Koshu and the Japanese seaplane tender Kamoi covered 150,000 square miles and continued until the 19th July. Amelia Earhart was officially declared dead on the 05th January 1939.

However, new evidence has shown that it's not as clear-cut as we have been led to believe. Apparently, after the search was concluded, post-loss radio signals from Earhart and Noonan were treated as hoaxes and were consequently disregarded. And it is now believed that these signals were, in fact, authentic - they started to hit the air waves just hours after her last in-flight transmission.

The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) carried out an extensive investigation and, after making a thorough study of all 120 known signals presumed to hail from the marooned pilot, 57 were deemed valid. Very importantly, their study also concluded that the plane was standing on its wheels on land for numerous days after it vanished. This correlates very nicely with the post-loss signals, as it appears that the plane may well have landed on the island's reef and possibly stayed afloat for some days. Unfortunately, the general consensus at the time of Amelia's disappearance seems to have been that the plane had crashed into the ocean, therefore rendering the radio equipment useless. The radio system could only work if the plane was on dry land or above water. Therefore, it follows that any post-loss signals would have, sadly, been ignored and treated as bogus.

It's certainly heartbreaking to learn that on one of the last distress signals sent out by Amelia she alludes to rising water. And one week after the aircraft vanished, three US Navy planes flew over Gardner Island and didn't see anything. Of course. The distress calls had already ceased.

Additionally, weather-permitting, it would have been feasible for her signals to be received in the central Pacific. In fact, the USCGC claimed to have heard this kind of signal once. According to TIGHAR, there were a minimum of four important signals supposedly heard by more than one station.

Earhart had been officially missing for only five hours when the USCGC, the Achilles and the SS New Zealand Star reported to have received the first signal. The USCGC were unable to fathom the content of the message as it was “very weak and unreadable” so they asked for Morse code instead and soon received a stream of dots and dashes in reply.

Another signal received by the US Navy Radio at Wailupe, Honolulu on the 05th of July was broadcast in Morse code as follows - “281 north Howland – call KHAQQ – beyond north – won't hold with us much longer – above water – shut off.”

Then, simultaneously, a strange code with the letters KHAQQ again came through to an amateur radio operator in Merlbourne, Australia.

KHAQQ was Amelia Earhart's call sign...

As Ric Gillespie from TIGHAR put it - “The results of the study show a body of evidence which might be the forgotten key to the mystery. It is the elephant in the room that has gone unacknowledged for nearly 75 years.”

On an expedition in 2012, TIGHAR discovered various artefacts on Nikumaroro Island (Gardner), where Earhart and Noonan may have been stranded. The most notable of these recoveries was a selection of glass fragments. When put together, they formed a jar almost identical to one that Amelia apparently was never without – Dr. Berry's Freckle Ointment; this cream purportedly faded freckles, which Amelia had and didn't like.

And this wasn't the only remarkable discovery made since the famous pilot vanished. In 1940, a British official found a quantity of bones interred close to the remnants of a campfire. When the bones were analysed, the examining doctors came to differing conclusions. One said that they belonged to an elderly Polynesian male, while the other reckoned they resembled those of a European male. Strangely, the bones later vanished (Deliberate? Constant attempts at hiding the truth?). However, the measurements did survive and, when they were tested by forensic anthropologist Richard Jantz, he determined that “the evidence strongly supports the conclusion that the Nikumaroro bones belonged to Amelia Earhart.” Well well...

The human remains weren't the only discovery in 1940. A piece of both a man's shoe and a woman's shoe, a box that once housed a sextant and various small animal bones were also found. All these other articles point inescapably to a castaway's camp.

Just a year and a half after Amelia vanished, Nikumaroro Island (Gardner) was colonised by a group of Pacific islanders. Because of an extreme drinking-water shortage in 1963, the natives were forced to leave. And here's the curious thing. Sometime after, during archaeological activity on the deserted settlement, it was discovered that the villagers had obtained debris from a plane, which they had cut up into pieces and utilised. And, not surprisingly, a number of these Plexiglas and aluminium fragments are compatible with the Lockheed Electra...

As recently as last December, forensic scientists spotted concealed markings on an aluminium panel recovered on Nikumaroro Island in 1991. The carvings consist of letters and numbers and scientists believe they could be manufacturing codes. They are currently trying to track down the source. If it comes to light that this panel came off Amelia's Lockheed Electra, well … I guess the mystery would finally be solved. We would then know for sure that Amelia Earhart was marooned on Gardner Island (Nikumaroro) and ultimately died there.

“I have often said that the lure of flying is the lure of beauty”

.png)